You know how you have chemistry with certain people? When you meet them, you instantly feel the spark; you can sense that this is a person who will be in your life for a long time, far longer than just this handshake or hug. I believe that you can have chemistry with certain places, too. You arrive in a new place, and well before you can assess your surroundings with observation or logic or reason, your body chimes with a note of resonance. Yes, you think, or rather, you feel. Yes, I like it here.

Up until a few weeks ago, I’d only been to London once before, during a brief visit in 2017. But even on that brief visit, I felt an instinctive love for the city, an immediate desire to return. A few weeks ago, I finally managed to get back, and happily discovered that my instinct from six years ago had been correct.

I love London. I just love it! I don’t really know the city well enough to engage in any kind of compare-and-contrast exercise, so I’ll spare you from any haphazard conjecture about whether New York or London has the better food, whether one is more cosmopolitan than the other, etc. What I will tell you is that spending time in London, especially during this recent visit, is, for me, an experience of expansive dreaminess. Speaking the language means I can walk around the city with a certain degree of familiarity and intimacy, but London is also a new and unfamiliar, and occasionally disorienting. London, for me, consists of familiar elements arranged in an unfamiliar way, rather like a dream in which you encounter your childhood bedroom in the middle of Times Square.

I landed on a Tuesday morning and met my mom at our Airbnb in Marylebone, where my sister would also join us a few days later. The week I was away would prove to be one of biblical rain in New York, but it was mild and sunny in London, my raincoat and umbrella sitting unused in my suitcase for the entire trip. I was starving when I landed, so my mom and I beelined to the nearby Ottolenghi and picked up lunch to go. We were walking to a nearby park when, bleary with jetlag, blinking into the sunshine, I had to do a double-take. Across the street was an old friend from publishing, my friend K., someone I hadn’t seen in probably eight or nine years. Our bookclub used to meet in K.’s studio apartment on the Upper East Side, an apartment I can picture with the sharp clarity that marks so many of my right-out-of-college memories. But, you know how it is. Life goes on, jobs change, neighborhoods change. K. and I fell out of regular touch, but there, on that sunny day in London, both of us thousands of miles from home—there we were! It was surreal and totally delightful.

The next day, after a slow start, my mom and I set out for a long walk toward the Thames and across to the Tate Modern. I picked up a peach from a little shop around the corner, and ate it while strolling through St. James Park. It was easily the best peach I’d had all year, like a perfect slice of high summer in late September. When we walked into the atrium of the Tate Modern, the first thing we saw was a crew of hard-hatted workers in a cherry-picker, installing two new pieces by El Anatsui, a pair of massive tapestries made from discarded bottle caps. This too felt a little surreal, watching these workers perform the delicate task of installation using the machinery that one associates more with heavy-duty construction.

We spent several hours at the museum, then walked home, and after a short rest, headed to the West End to see Andrew Scott, aka the Hot Priest, starring in a one-man version of Uncle Vanya. It was a one-act show in which the Hot Priest played more than half-a-dozen characters. Watching him morph from one character to another with liquid physicality was like some kind of riveting sorcery.

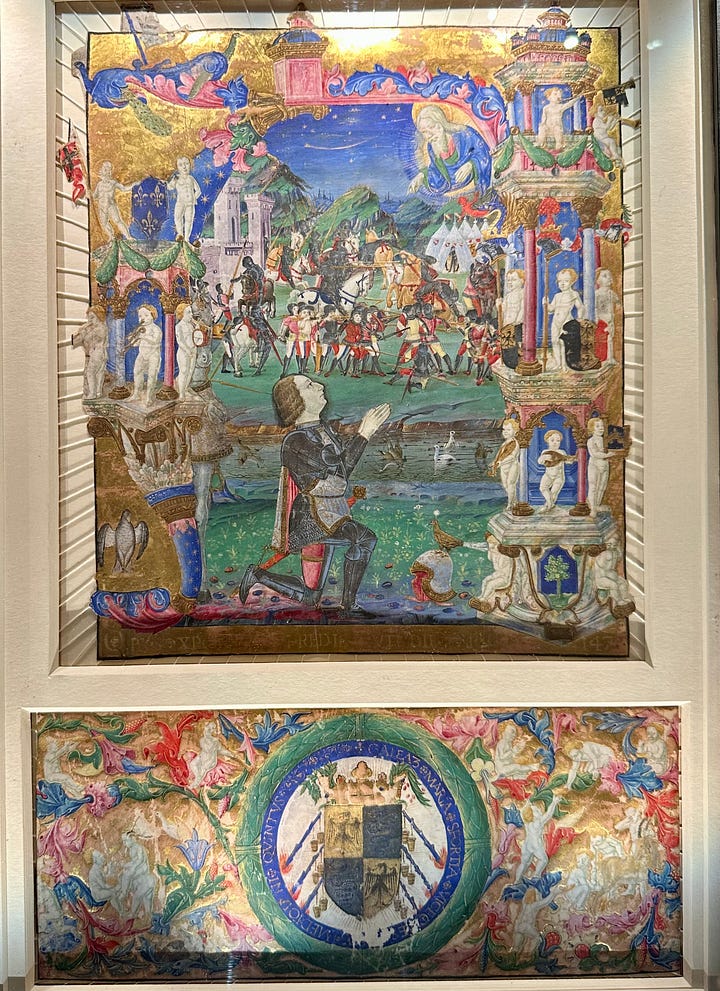

The next day my sister joined us. As she was napping post redeye, my mom and I wandered over to the nearby Wallace Collection, which had come recommended by my dear friend S., a fellow novelist who lives in New York. Near the entrance on the the ground floor were galleries housing an extensive collection of miniatures, tiny squares and ovals of vellum, exquisite little renderings of knights and nobles and other figures from history, both real and mythical.

Now, look. Normally miniatures don’t really do it for me. Given me an Impressionist! Give me an Abstract Expressionist! Let me lose myself in the beautiful freedom of a Joan Mitchell, which was in fact exactly what I had done the day before, at the Tate Modern. Give me that freshness, give me that movement! But during that morning at the Wallace Collection, for whatever reason, I just couldn’t tear myself away from the miniatures.

The museum keeps their miniatures in glass cases at waist height, the glass shrouded with leather coverings to protect the miniatures from sunlight. You lift the leather cover from the glass, press a button on the side of the case, and turn on the light inside the case so you can see better. The light is on a timer, and turns off after a minute or so. I kept wishing the timer lasted longer. I was bent low over the cases, mesmerized, pressing the button over and over.

What was it about them? In the moment, I couldn’t tell you. I was enchanted; that was enough. But now that I’m home, and looking back on our time there, I find myself wanting to think more about this attraction.

My friend S., the fellow novelist who had told me about the Wallace Collection, she’s of my favorite people to talk through creative problems with. She understands my half-baked ideas, the gauzy metaphors that often drift into my mind. Earlier in the spring, when I got back from Switzerland, we went for a walk and I told S. about a feeling I’d had while sitting in the Grossmunster church in Zurich, and how this feeling connected to the book I was working on.

The Grossmunster, now a Protestant church, started life as a Catholic cathedral. Construction of the cathedral began around 1100 and took over a century. It’s now quite an austere space, the interior stripped of ornamentation, but there remains a magical quality. You sit there, in the wooden pew, and you can feel how long it took to build this structure. You can feel the care and planning and deliberation that went into it. What I felt wasn’t a religious feeling—rather it was gratitude for the time and attention given by the architects, by the planners, by the builders, by those who hauled the stone and metal and glass. Even centuries later, the space retains the imprint of that care, of that work, of that deliberation. If you sit there and let yourself get quiet for a moment, you can feel it.

I came back from the trip and told my friend S. that I want to write a book that gives the reader the same feeling that sitting in that cathedral gave me. I want to invest a great deal of care and time and attention into the work. I want to create a container in which the reader can rest for a while, feeling held, feeling cared-for. I want to give the reader a space to hang out, a space that can lift them outside of themselves for just a little while.

This desire has probably been within me all along. Why do I write novels, after all? I write novels to escape the heavy fetters of my own reality. I write novels to seek freedom from my limited self. I write novels to lend that same sense of temporary freedom to the reader. This desire has always been true, but it wasn’t until earlier this year, after traveling to Switzerland, that I began to see this wanting within myself, to understand it more precisely for what it was.

Back in the spring, as I recounted this feeling, S. understood exactly what I meant. The novel-as-cathedral. It was the metaphor I couldn’t stop thinking about.

Now, a miniature might seem to be the very opposite of a cathedral. But last week, as I stood transfixed over those glass cases, the art gave me the same feeling as did the Grossmunster in Zurich. The scale is a lot smaller, a lot smaller, but the care and attention is just as evident. The unbelievable fineness of the brushstrokes. The exquisite details of the fabrics, the faces, the hands. An entire story distilled into just a few square inches. Looking at a miniature felt like looking at a whole world. Even after leaving the miniature gallery and exploring the rest of the museum, I found myself drawn to the details. I stood for a long while in front of a Canaletto painting of Venice. I kept zooming in on the different groups of figures scattered across the canvas. The people in the piazza, in the gondolas, in the balcony of the palace: each was another seed for my curiosity. What are those people talking about? I wondered. And what about them, over there?

Later that day, I texted S. to tell her how much I loved the Wallace Collection. I told her to remind me, the next time we hung out, to tell her more about how those miniatures made me feel, and how I want fiction to make me feel that way, too.

Back in 2015, when I was querying agents with the manuscript for my first novel, the novel that would become The Futures, I received many (many!) rejections. Most rejections were polite, and usually the agents were kind enough to share a reason. I know from my publishing days that often these reasons are pretty half-baked (you say something because you have to say something), but one piece of feedback has stuck with me through the years.

One agent told me that, while they enjoyed aspects of the book, they found themselves wishing the story was more densely populated. I had written a novel focused almost entirely on the realities of college sweethearts Evan and Julia. Of course there were supporting characters, friends and coworkers, sidekicks and villains, but none of them quite had their own reality, not in the way the narrators did. This agent liked the premise, but they were looking for a story with a greater number of fully realized characters.

I remember thinking to myself, Lol, but, like HOW? It took me three years to come up with just these two characters! Two was hard enough! It felt like I had just finished running a marathon and this agent was saying, casual as could be, Hey, how another 26.2?

We all have selective memories. That which sticks with you sticks with you for a reason, the memory attaching itself to something buried inside of you. Eight years and four books later, I’m still thinking about that piece of feedback. When I was just starting out, I wasn’t capable of building a structure that felt as vast and solid as a cathedral. Nor was I capable of rendering detail that felt as exquisitely specific as a miniature. I’m still not sure, to be honest, whether I’m capable! But I’ve remembered this feedback because, on some level, this has been my goal all along. And in the new book I’m writing, I’m determined to try.

The novel I’m currently writing, the one that will follow The Helsinki Affair (Friendly reminder that the book comes out on November 14! PREORDERS ARE MY LOVE LANGUAGE!), is the sequel to Helsinki. As I write my way through it, I’m taking so much pleasure in being with these characters and in this world again. Amanda and Kath, Charlie and Maurice, I know them as intimately as I know anything. But also, in this new story, they keep surprising me. I keep finding them in places that I didn’t expect. The familiar keeps overlapping with the unfamiliar. The dream comes from me, and like in any other dream, I only have so much control.

Before I say goodbye, my letter of recommendation for you: I’d been hearing the buzz about Caroline O’Donohue’s novel The Rachel Incident for many months now, and I finally got around to reading it. This book! It’s so much fun. It’s about a pair of broke-ass 20-something best friends trying to scrape their way into adulthood in post-financial crisis Ireland, with various romantic entanglements and errors along the way. It was so funny, and so tender, and so beautifully specific. There’s been a lot of ink spilled in recent years on the sub-genre of the “millennial trainwreck novel,” a genre of which Sally Rooney is the patron saint, a genre in which The Rachel Incident might be lumped. Admittedly I have not read very many books in this genre. It’s not necessarily my thing. But this book! I just loved it.

I sometimes draw a similar connection with song lyrics. Some are big and expansive and you can spend a lifetime vicariously inhabiting the world of artists like Dylan, or Van Morrison, or Joni Mitchell. But there are others, like some of the best country writers, who feel like they work in miniatures-- rich stories told on tiny canvases, like seeing a whole world through a peephole. Definitely want to check out the Wallace Collection-- wasn't at all familiar with it.

Oh, how I love me some London! And your family too! x