Coffee With ... Hannah Sloane

A debut novelist on the eve of publication discusses her pandemic writing routine, the luxury of being edited, and the people who make it look easy (even when it isn't).

Hi, friends! A quick note from me, before we get into it. Today’s newsletter is the first in what I hope will become an ongoing mini-series about the writing life. Talking shop with fellow writers is one of my favorite things in the world. I get so much out of those conversations—they always, without fail, help me to better understand my own process—and it struck me that other people out there might also get something out of them. And so I’m giving this a shot!

I’m hugely grateful to the novelist Hannah Sloane for being my first participant in this series. This format may evolve along the way, but for now: I really enjoyed talking with Hannah, and I hope you’ll enjoy it, too. —AP

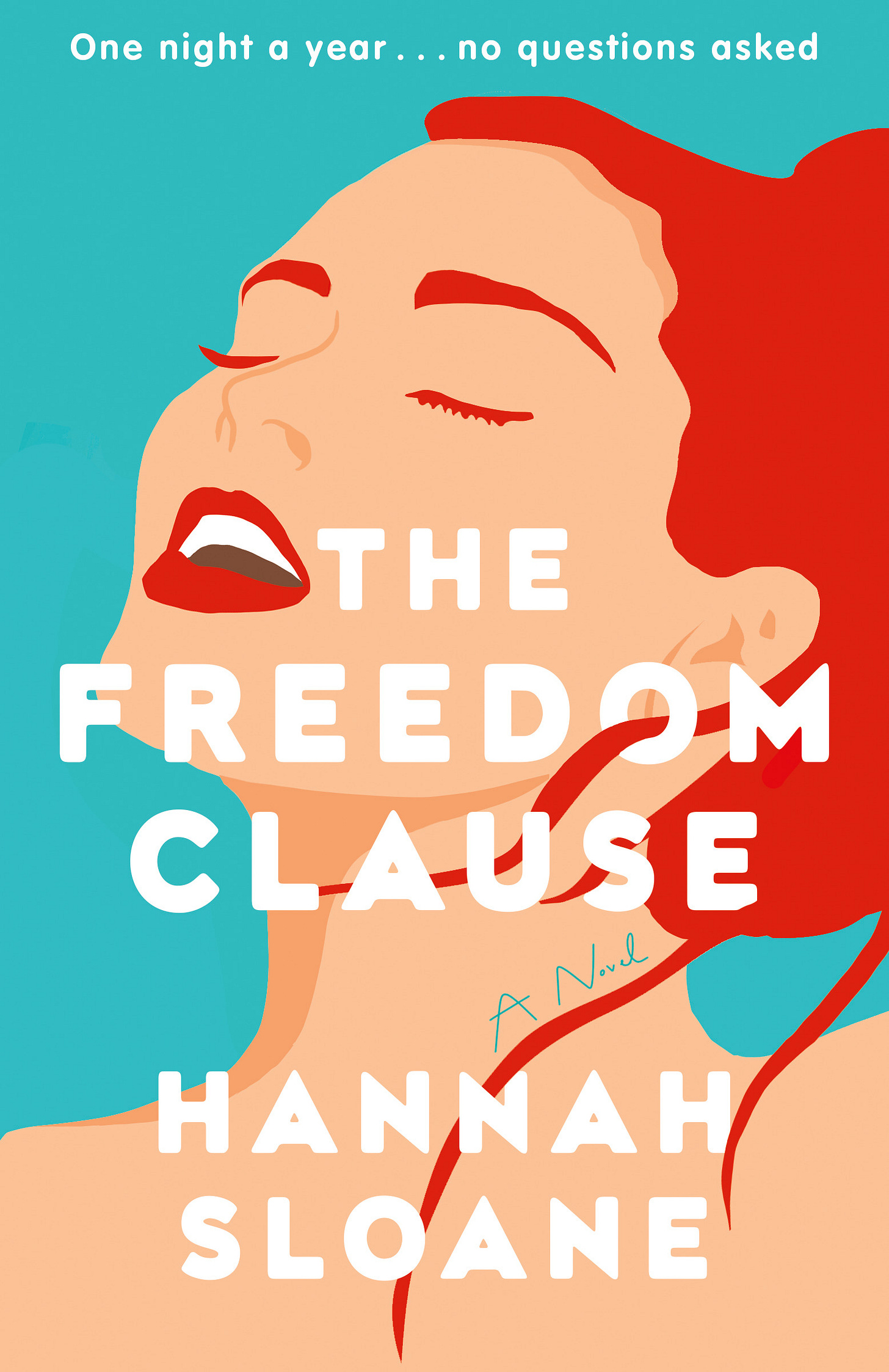

Hannah Sloane is the author of the debut novel The Freedom Clause, which Dial Press will publish on July 25. Carola Lovering called the novel “saucy and smart,” and the New York Post has chosen it as a top summer read. I first learned about Hannah’s novel through her editor (aka my friend and former co-worker!) Emma Caruso, and I was so delighted to spend an hour chatting with her. We talked about the anxieties of releasing your work into the world, the lessons of being edited, the pleasures of deep-sea diving into fictional worlds, and much more.

The transcript of this conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity, and also so you don’t have to hear my parents’ dog barking in the background.

ANNA: Hannah, your novel comes out in just a few weeks. Could you start by telling us what the book is about? I’m also wondering—how are you feeling, in this moment?

HANNAH: The Freedom Clause is about a young British couple who decide to open up their marriage for one night a year, over a period of five years, and the unexpected revelations that come from a woman learning to ask for what she wants.

I wanted to write about a young woman who tends to be a people-pleaser, and how her journey of sexual self-assertion plays out in other areas of her life. It's a book that gives women permission to live their lives fully on their terms, by ignoring societal pressures, and focusing on what they need. It’s a theme that's very close to my heart.

As for how I'm feeling… a lot of excitement to put my book out there in the world. There’s the anticipation of who will read it, who will connect with it, but I have nerves too. There's a lot, as a writer, that you can control, but not at this stage. I've got to sit back and enjoy this moment, which admittedly I find hard to do. I'm a control freak!

I think us writers are inherently a little control-freaky. We get to play God with these characters, we dictate what happens. We work in private for such a long time, but then we have to let the world render a verdict. It’s hard!

Definitely. And the temptation is to go through the GoodReads reviews…

Oh, God, I know.

A friend told me: “do not read your GoodReads reviews. You are eavesdropping on a conversation not intended for you.”

Have you managed to mostly adhere to that advice?

Let’s just say: I am much more disciplined now. I saw the novelist Hanya Yanagihara speak at an event last year, and she said she never reads the reviews because someone once told her: “the good ones aren't good enough, and the bad ones will stay with you forever.” What about you?

For me it’s most tempting at the beginning, just as the galleys are starting to circulate. That's when I tend to check and see what people are saying. I think I’m looking for reassurance, and probably validation, too, to be honest. But after that first hit of public feedback, I tend to get less curious about what people are saying online.

I’d love to rewind the tape for a moment and talk about where your writing journey began.

It began over a decade ago. While The Freedom Clause is my published debut, I wrote another novel before this one which helped me find and secure my agent. I worked on that first novel for about eight years, which sounds like a long time, but I wasn’t particularly disciplined about writing back then. I had a very whimsical approach to it, only doing it when I was one hundred percent in the mood (which wasn’t very often).

When I consider that manuscript now, I can see it didn’t have a strong sense of plot. There were viewpoints from too many different characters. It took place across four continents. There were flashbacks, possibly even (oh god, bear with me here) a dream sequence. Ultimately, that manuscript didn’t sell and I see why. I see the (many many) flaws in that manuscript.

But I credit that process with helping me reach this point. I learned so much through that process which I channeled into this novel. This time, I was very disciplined. I started writing in March 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic. I was living alone, I wasn’t going out much, and I just kind of gave everything to it. Doing Jami Attenberg’s 1000 Words of Summer that summer helped spur me along too.

Oh, she’s great!

She is. Before joining that program, I’d written maybe one or two chapters, and I kept polishing them on repeat. What’s great about Jami’s program is that it forces you to pick up the pace, to move away from the stasis of perfecting your early scenes. I started her program in the summer of 2020, writing one thousand words a day for fourteen days straight. By the end, I had another six or seven chapters and it was beginning to resemble a novel. Encouraged, I kept writing one thousand words a day. It became my own personal project.

I’d finished the book by the end of that year. Then I sent it to my agent, and we worked on it together for another nine months. She sent it to publishers in the fall of 2021, and within about a month, we had two publishers that were interested, and we went with Dial Press.

It was a relatively quick process, but I’d spent a lot of time mulling over the storyline before I began to write, unlike with my first novel. I thought about the plot, what would be driving the conflict, and the two main characters, what their narrative arcs would be.

Was it a deliberate decision to take your time, thinking through the story, before you actually started to write?

It was. And while I would love to say it came from a place of strength, it in fact came from a place of fear. I didn’t want to spend eight years on this novel.

And when I finally started writing this novel, having stewed on the plot and characters and their motivations for quite some time, the story really flowed out of me in a magical way. I don’t know if I’ll be able to repeat that experience with future books. I hope to, but I sense it may have been a beautiful, one-off occurrence.

It’s interesting. The pandemic was, of course, very difficult, but for some people, having that sudden excess of time actually created a productive kind of energy. I found that the novel I wrote during the pandemic also just kind of … came out of me. There was a flow and fluidity to it.

Definitely. Gary Shteyngart wrote a piece for Lit Hub where he said the pandemic was perfect for his writing because there was nobody to get drunk with, and his productivity went through the roof. I remember thinking how true that was!

During the pandemic, my writing went well. Reading, on the other hand, did not. I found it very hard to read, to focus, especially during that early part of the pandemic. I think it came from a place of anxiety. I found it hard to sit still and focus on someone else's world. But that was okay since, like I said, the writing was flowing beautifully.

Can you remember the book that eventually got you out of your pandemic reading rut?

Unusually for me, I gravitated more towards essays. I read Notes to Self by Emilie Pine which is excellent, and What My Mother And I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate. I think it was Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stewart that finally broke me out of my fiction reading rut. I love those heartbreaking, all-consuming novels, like Shuggie Bain and A Little Life. Another book that I completely fell for during the pandemic was Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason. That book is so special. It’s beautifully sad and hilarious at the same time. I’m so envious of people who can do that, who bring out both reactions in their readers.

That seems to be a little bit of the spirit you’re capturing in The Freedom Clause.

I hope so. There are funny parts, but the characters also go through a lot of personal growth that comes from certain hard realizations.

How similar—or different—is The Freedom Clause to the first novel you wrote, in terms of thematic preoccupations?

They’re both novels about relationships under duress. That’s a theme I’m drawn to. My first novel was about a couple in a long-distance relationship; he was based in Tokyo, she was in New York, in which they become increasingly estranged from one another. The Freedom Clause is about a couple whose relationship has grown stale, at least sexually, so they decide to open up their marriage, for one night per year, for the next five years. The novels have certain similarities, but The Freedom Clause feels much tighter, more focused.

And there's a built-in structure to it, with the decision to have this be one night per year for the next five years. I think that's very smart. Because, as a writer, the feeling of being able to take the story in any direction, without any structure or limitation—it can be paralyzing.

Yes, you're right. There’s a chapter for each of the five years, plus a prologue and epilogue, and this structure made it much more manageable to write, and then edit.

And it was interesting working with an editor. I remember, when I signed with Dial Press, thinking, Oh, the hard work is done, it’s going to be a breeze now! But the editing process is extremely rigorous. My editor, Emma Caruso, is fantastic. She brought so much energy and enthusiasm, and so many ideas to the table. It was a little intimidating, but ultimately worth it. When I look at the manuscript that was sent to them initially, and where it is now—it’s amazing, having an editor. It's such a luxury.

It's a luxury, and also a necessity. When I look at the version of The Futures that we submitted to publishers, or the version of The Futures that I submitted to agents, it’s so wildly different from the finished product.

Writing my first novel was probably fifty percent of how I learned to write a good novel. But being edited was probably the other fifty percent. If you’re lucky enough to work with a sharp editor, you can, hopefully, internalize some of their feedback, and bring some of it with you into the next book. Did you get some of that insight into your own craft during the editing process?

Absolutely. My editor helped improve the pacing. She immediately saw which scenes were unnecessarily slowing the plot down. Also, she was very good at identifying what was holding characters back. As a writer, when you’ve created this world, it’s hard for you to see when the character’s flaws go too far, or where a scene slows you down.

The way I’d written the story, the male protagonist created most of the conflict and drama, and it was a tricky balancing act, having him create conflict, but still ensuring that the reader stayed with him, rooted for him. Emma would say: “we need to make this male character more likeable.” My response was: “Oh, but I think he is now.” And at one point she had to highlight throughout the manuscript sections where I was plainly wrong. She’d write comments like: This puts me off. Why would he say this? And that was the only way I could see it. Again, what a luxury to have an editor holding your hand, and guiding you in this way.

I really listened to Emma. Like, I'm a first-time novelist here, and she’s a seasoned hand. Another example is that, by the time we finished the book, the opening chapter was completely different from the first draft. It’s good to remember that you don’t need to have the ultimate beginning or ultimate ending. It’s best to be open to change throughout the process.

It sounds like, based on your description of writing The Freedom Clause, that you hadn’t necessarily mapped the story out, beat by beat, before you began.

Exactly! I knew the beginning of the book, and I knew the ending, and what the narrative arcs of the two main characters would be, but I hadn’t figured the middle part out, and what was surprising was how naturally the characters dictated some of those middle scenes to me.

When I started writing, I was nervous that I didn't have the characters fully fleshed out. You read advice suggesting you should know everything about your character: their star sign, their favorite food, where they grew up. I didn't start that way and what was wonderful is how the characters fleshed themselves out, developing very distinct personalities before my eyes. It was fun. And I was spending so much time with them, it was kind of like they became my friends.

I think a character can become very real to their creator. To the extent that, if I've had a really good writing session, if I've been deep in it, I’ll stand up from my desk, and go to the kitchen to get lunch, and I have this weird sense of non-reality. Like, Oh, that world I just left actually feels more real than this kitchen I’m standing in.

Yes, definitely. That’s my favorite part of writing, the immersive aspect. It's like going deep-sea diving and when you return to surface, when you pull out of the manuscript you think: Wow, those last five hours flew by. What's strange, at this point in the process, is that I am not deep-sea diving in the world of this book. I turned in final edits last summer, and now I feel quite distant from those characters, and that entire world. I couldn't tell you the exact flow of certain scenes. I could reread the book to remind myself, but instinct tells me not to, that that's not healthy. The healthy move, I suspect, is to let go of the book, and leave it with others to immerse themselves in that world.

Instead, I’m reading a lot. I’m rediscovering the joy of reading, especially after the last couple of years when I was so immersed in The Freedom Clause that I didn’t have much spare time to immerse myself in the worlds of other authors.

I think the reality-immersion of writing your own fiction is the strongest form of escape, but reading is the next best thing. I’ve been reading a lot at the beach this summer. The great thing about reading is that you can do it outside, which you can’t do with watching TV.

Absolutely! It’s the best feeling, when you just can't wait to go back into the world of the novel you’re reading.

Before we wrap up: You’re right on the eve of publication. If you could go back in time and give some advice or insight to the Hannah of three years ago, who was just beginning to write this book—or even further back, to when you were writing your very first novel—what would it be?

I would tell her that writing takes hard work. It’s a skill, for sure, but it’s so much about a commitment of time and effort. I would give her the advice to keep going, even as she received rejections, to trust that those rejections were getting her closer to acceptance. I could have stopped after my first novel was passed on by publishers, and I’m so incredibly glad I didn’t.

It's something my husband has observed. That the only difference between someone who has written a novel and someone who hasn’t written a novel is just, actually, sitting down and doing the work of writing a novel. I think it’s easy to discount the role of that perseverance and hard work.

It’s true. Last year, I was setting my alarm very early, like in the 4 a.m. hour, to edit for a few hours before doing my corporate job. I wouldn't change that energy and focus and hard work for the world. I think the “strong work ethic pays off” mindset applies to every industry. The people who are successful, the people who make their jobs look easy, are actually incredibly hard workers. They work harder than anyone. You just know that Beyonce and Taylor Swift work round the clock. And I’m going to drop a Bravo reference in right here because why not?! I’ve said it to friends before: “you know, Andy Cohen makes his job look really easy, but I bet it isn’t.”

It’s like going to the ballet and watching a dancer execute a gorgeous pirouette. It looks ethereal, like a kind of magic, but they have been freaking working at this for decades. Writing a novel is this interesting transmutation of effort into effortlessness. Like, the hard work that goes into writing a novel eventually results in this finished product which, hopefully, allows another person to disappear into the story. You’re doing all this work so that someone else, somewhere in the future, might feel this total sense of effortless escape.

And don’t you think sometimes that’s the reason you became a writer? It’s because, as a child, you picked up a book, and you loved it, and you thought: I want to create a world that readers can fall into and love like this? You kind of pay it forward.